22 July, 2019

By SJA Jafri

DILI/ MELBOURNE: Neither the Chinese themselves nor rest of the world could understand Communism and none of one state of the world especially India and Pakistan are ready to realize their real enemies while both countries are still unaware about Chinese concealed and open plans completely and are being misused because of their countries’ poor financial position, agitation, sectarian and religious intolerance, nations’ poverty and ‘pay-rolled leaders or rulers’ (those always either elected or selected by an idiot hidden world mafia) misusage and as China has been captured 47 percent of the world by land and sea and 66 percent financially and commercially. PMI has made an exclusive investigative report in this connection with solid figures and authentic evidences which would be published after dual verification.

DILI/ MELBOURNE: Neither the Chinese themselves nor rest of the world could understand Communism and none of one state of the world especially India and Pakistan are ready to realize their real enemies while both countries are still unaware about Chinese concealed and open plans completely and are being misused because of their countries’ poor financial position, agitation, sectarian and religious intolerance, nations’ poverty and ‘pay-rolled leaders or rulers’ (those always either elected or selected by an idiot hidden world mafia) misusage and as China has been captured 47 percent of the world by land and sea and 66 percent financially and commercially. PMI has made an exclusive investigative report in this connection with solid figures and authentic evidences which would be published after dual verification.

Oil and gas is Timor-Leste’s ticket to prosperity. Is this impoverished nation blowing its one chance?

Oil and gas is Timor-Leste’s ticket to prosperity. Is this impoverished nation blowing its one chance?

At Xanana Gusmao International Airport on Timor-Leste’s picturesque south coast, a morning flight comes in to land.

In fact, it is the only plane scheduled for the day. The next regular flight will not be for another four days.

As the 15 passengers collect their bags and leave, the airport empties into a silent, cavernous shell.

Inside, the check-in desk is unstaffed. The X-ray machine at immigration is switched off.

The empty departure lounge gleams with new chairs that look as if no-one has ever sat in them.

There is not a soul in the VIP lounge.

There is not a soul in the VIP lounge.

It has been like this since the airport opened in 2017 at Suai, in Timor-Leste’s remote south-west.

“At the moment it’s just lying empty. There is no real scope for any real air traffic coming through there,” says RMIT University academic James Scambary, an authority on Timor-Leste.

At a cost of $120 million, some wonder why the airport was built at all.

“There are much more sustainable, equitable and beneficial ways to spend that money,” says Charlie Scheiner from La’o Hamutuk, an independent NGO that monitors economic development in Timor-Leste but it is not only the airport that has raised eyebrows here.

Barely a kilometre away is a four-lane ‘super highway’ built by a Chinese consortium at a cost of around $500 million but it is a road to nowhere. The 33-kilometre highway connects Suai to a bumpy dirt road that leads to a few small villages surrounded by farmland.

Barely a kilometre away is a four-lane ‘super highway’ built by a Chinese consortium at a cost of around $500 million but it is a road to nowhere. The 33-kilometre highway connects Suai to a bumpy dirt road that leads to a few small villages surrounded by farmland.

And wet season rains have rendered the highway virtually unusable.

A massive landslide at one end has completely blocked the east-bound lanes since January.

Further along, a huge chunk of road has collapsed, forcing what traffic there is to drive on the wrong side both the airport and highway are, for now at least, ‘white elephants’: built at a huge cost but of little use.

They sit incongruously surrounded by small towns, vegetable plots and virgin forest.

They sit incongruously surrounded by small towns, vegetable plots and virgin forest.

However, Timor-Leste regards both projects as key to its long-term economic future.

Timor-Leste gambles big on oil and gas

The airport and highway are part of a massive infrastructure project to develop the entire south coast called the Tasi Mane project.

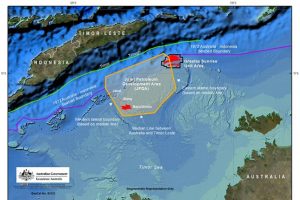

The plan is to pipe billions of dollars of oil and gas from the Timor Sea to process onshore.

It is Gusmao who has led the Tasi Mane project, which the Government hopes will gather momentum once Timor-Leste and Australia ratify the maritime border treaty next month.

The treaty will grant Timor the rights to most of the royalties from the still undeveloped Greater Sunrise field, valued at about $50 billion.

The state-owned oil company Timor Gap believes it is worth far more.

The state-owned oil company Timor Gap believes it is worth far more.

“Our figures show it’s more than $76 billion, based on the reserves that we calculated,” its CEO Francisco Monteiro says.

“We are set to receive over the life of the project at least $28 billion but critics say the cost of the project will far outweigh the returns.

East Timor is almost wholly reliant on oil and gas for its revenue but rather than pocket the royalties from offshore processing without spending a cent, as it does with the existing Bayu Undan field, it is determined to build its own facilities.

The Tasi Mane project includes plans for an LNG plant, a refinery, an industrial base, seaports, a second airport and a highway linking them all along the entire south coast.

All of this will require an outlay of up to $16 billion.

All of this will require an outlay of up to $16 billion.

That is roughly equal to the amount now sitting in Timor-Leste’s Petroleum Fund — the same fund that pays for the Government’s annual budget to cover health, education and other vital services.

On top of this, Timor has separately paid $650 million to buy a majority stake in the Greater Sunrise project, giving it control over how — and where — the oil and gas are developed.

Timor Gap is now trying to source $16 billion in loans from foreign banks and investors, including China’s Exim Bank but analysts and many in the petroleum industry say the project is simply unviable, will create few real jobs for Timorese workers, and could send East Timor into a Chinese ‘debt trap’ if the project fails.

“Betting the entire resource endowment, the $17 billion that is saved in the Petroleum Fund, on one project in the petroleum sector, is a bad gamble,” Scheiner says.

“Betting the entire resource endowment, the $17 billion that is saved in the Petroleum Fund, on one project in the petroleum sector, is a bad gamble,” Scheiner says.

Scheiner believes the petroleum sector is the least efficient way of creating jobs in Timor.

“We need to focus on agriculture, we need to focus on tourism, we need to focus on small industries to produce things that are used here,” he says.

Early this year, Timor’s Parliament passed amendments to whittle away some of the legislative checks and balances that were set up to stop politicians siphoning money from the Petroleum Fund for white elephant projects.

Timor-Leste’s leaders push ahead, but is it a pipe dream?

James Scambary questions the Government’s obsession with bringing the oil and gas to East Timor against all advice to the contrary.

James Scambary questions the Government’s obsession with bringing the oil and gas to East Timor against all advice to the contrary.

“The kind of attitude you get is: ‘Well, we won the war against the Indonesians. We won the dispute with Australia over the sea boundary, and you said we couldn’t do this. And we’ll do this too,'” he says.

Then there are the considerable technical challenges to the project, including the need to build a 286-kilometre pipeline across a 2,800-metre-deep trench near East Timor’s south coast.

A US bathymetric survey concluded that the pipeline would need to be heavier than any pipe ever laid, to withstand the pressure at such depth.

If the pipeline flooded, there would be an unacceptable risk that it might break. There would be no possible remedy because of the depth.

If the pipeline flooded, there would be an unacceptable risk that it might break. There would be no possible remedy because of the depth.

Even the Greater Sunrise partners have opposed the Tasi Mane project.

Woodside Petroleum, the joint venture operator, will not invest in the onshore plants.

ConocoPhillips and Shell have both sold their stakes in the Greater Sunrise project because of concerns about Timor’s ability to process onshore.

Despite this, a report prepared for the country’s state-owned oil company suggests the Tasi Mane project would generate around 12,700 jobs during construction and 2,000 ongoing jobs, “the majority of whom are expected to be Timorese”.

The report predicts a second construction phase would generate up to 12,600 jobs by 2028 but Scambary says Timor simply lacks the skilled workforce to build or operate an LNG plant or oil refinery.

The report predicts a second construction phase would generate up to 12,600 jobs by 2028 but Scambary says Timor simply lacks the skilled workforce to build or operate an LNG plant or oil refinery.

“It seems to be absolute fantasy. Most of the people who work there will be foreigners,” he says.

Critics say the Government has not invested in the kind of skills that they need to participate in the petroleum industry.

“There are no vocational training schemes required to build people up to [be] welders, fitters, boiler makers, technicians who work in these facilities. They just aren’t there,” Scambary says.

Locals lose hope that oil and gas jobs are on the horizon

Locals lose hope that oil and gas jobs are on the horizon

Even those who live closest to the Tasi Mane project have little faith that it will lead to jobs.

Leonel Amaral is one of hundreds of residents at Suai who agreed to sell his home and land to make way for the new airport.

In return he says they were promised their children would be given jobs at the airport.

“I wanted two of my children to work at the airport because I gave my land to the state,” he says.

Amaral says residents feel short-changed by the Government.

“We were offered $7 a square metre (for our land), then they reduced it to $4 but they only paid us $3 per meter,” he says.

“We were offered $7 a square metre (for our land), then they reduced it to $4 but they only paid us $3 per meter,” he says.

The residents now live in a newly built area directly next to the airport.

The street looks onto the runway, but with barely one plane a day, the noise is hardly an issue.

The residents acknowledge that the Government has also gifted them new homes here, built by an Australian company but the homes, they say, are more suited to a colder, Australian climate, and are too hot for comfort.

Many also complain they have lost valuable farm land.

“They abandoned us, didn’t pay money for what I lost,” Amaral says.

Despite everything, East Timor is determined to press ahead with the Tasi Mane project, confident the country will be on a winner once the royalties from Greater Sunrise begin to flow.

Timor Gap is projecting net profits of almost $45 billion over the life of the project, although the first positive returns after debt won’t be until 2030.

Timor Gap is projecting net profits of almost $45 billion over the life of the project, although the first positive returns after debt won’t be until 2030.

It is good enough for the CEO of the state-owned oil company Francisco Monteiro.

“Why would we ever think about failure?” he asks.

With one of the youngest populations on earth — the median age is 17 — officials fear unemployment could skyrocket in the next few years.

“The way to develop this country is industrialization. We can’t just live life as it is. If we continue to go on like this for another five to 10 years, we will be in trouble,” Monteiro says. (With ABC News)

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia