21 July, 2019

By Naseh Shaker {(Yemeni Freelance Journalist), Courtesy MEE}

By Naseh Shaker {(Yemeni Freelance Journalist), Courtesy MEE}

On rocky hillsides overlooking the Saudi city of Najran, Houthi fighters are waging an attritional campaign, even as nearby towns and roads are being pounded by air strikes

For three days Rafeeq al-Wadi and his cameraman trekked through the rocky mountain landscape towards Yemen’s border with Saudi Arabia, fearing all the time that they would be spotted by a reconnaissance drone or a helicopter gunship that could end their lives in seconds.

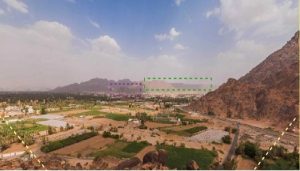

“Every day, from morning to evening, we walked on foot. I was 95 percent certain I would not return,” said Wadi, who asked not be identified by his real name because of security concerns, as he shared images with Middle East Eye which appear to show him overlooking the southern Saudi city of Najran, a microphone in his hand and an AK-47 slung over his shoulder.

Wadi, a Houthi military reporter, told Middle Eeast Eye (MEE) that the daylight footage was filmed during the Houthis’ reported raid into Saudi-controlled territory in the border region near Najran at the beginning of June.

Purported footage of the raid broadcast by pro-Houthi media showed the Yemeni rebels hitting armored vehicles with rocket launchers, and seizing abandoned military equipment.

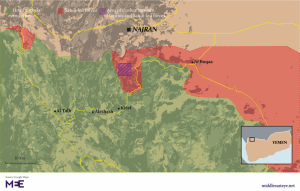

The Houthis claimed to have captured 20 military sites from both the Saudi National Guard and Saudi-backed mercenaries, and killed about 200 fighters aligned with the Saudi-led coalition, although MEE has been unable to independently corroborate these details.

The Houthis claimed to have captured 20 military sites from both the Saudi National Guard and Saudi-backed mercenaries, and killed about 200 fighters aligned with the Saudi-led coalition, although MEE has been unable to independently corroborate these details.

Most of the sites identified by the Houthis were in Yemeni territory adjacent to the border and under the control of Saudi-led forces. Saudi forces responded with rocket fire and shelling, and also launched air strikes deeper in Yemeni territory.

Wadi told MEE that the sites seized in June remained under Houthi control and that a Saudi counter-offensive had been disrupted by a Houthi missile strike on a military camp on Sudais Mountain, inside Saudi territory and only a few kilometers from Najran city.

Wadi said the place where he was standing was on the Yemeni side of the border but was in territory which had been under the control of Saudi forces since before the Saudi-led coalition intervened in Yemen in 2015.

A comparison of the footage with Google Maps satellite imagery suggests he is overlooking the outskirts of Najran from a hillside to the southwest of the city.

The attack formed part of a more aggressive strategy by the Houthis in the border region which has seen them set Saudi territory ablaze with a series of drone and missile strikes, hitting Abha airport in the south of the country several times in recent weeks.

‘We drive on roads fearing Salman’

‘We drive on roads fearing Salman’

MEE spoke to Wadi in the town of Aleshash, about 60 kilometers from the border and as close as this reporter was able to get to the frontier after securing rare permission from the Houthi authorities to travel northeast from Saada into one of the most contested areas of the country’s civil war.

Yet, even in the relative safety of Aleshash, we sit under an overhanging rock face as we talked for fear of a drone attack.

Reporting in this region, where the Houthi have been fighting since 2004, first against the pro-government forces of former president Ali Abdullah Saleh and since 2015 against the Saudi-led coalition supporting the government of President Abd Rabbuh Mansour Hadi, is tightly restricted. Beyond this point, everything is considered a military zone.

My driver, Abu Hakim, a local Houthi fighter in his thirties, is assigned to me by the authorities, who also provide the Toyota pickup for our journey.

Wadi and another Houthi minder accompany us, and even taking photographs of the landscape requires their permission. When I fail to do so, I am ordered to delete the images. My interviews with local people are also monitored and recorded.

The Houthi slogan, “Allah is Great, Death to America, Death to Israel, Curse the Jews and Victory for Islam,” is everywhere we go, daubed in paint onto walls and rocks, a constant reminder of who controls this territory in defiance of the formidable and largely US-manufactured firepower available to the Saudi-led coalition.

Despite the damage caused by the war and the ever-present threat of air strikes, there are plenty of other travelers on the road, but few are willing to stop and talk.

Arriving at Oseillah bridge in the Noshour valley in the Al Safraa district, about 30km north of Saada, the bomb-damaged crossing is impassable and a queue of vehicles including buses and trucks wait to bump along a rutted and unpaved track.

“We drive on roads fearing Salman,” said Faid Mosali, a truck driver, leaning out of the window to peer through the dust, referring to the Saudi king’s warplanes.

Cameras and guns

Cameras and guns

“I felt a great joy,” Wadi said, recalling the moment he had first looked down on Najran. “I feel satisfied now to have captured these images to show to all Yemenis.”

Gesturing towards his camera, he added: “This is my most powerful weapon.”

Wadi, a 32-year-old former English teacher with three children, signed up to work as a cameraman for the Houthis’ media arm after the school where he was working in the Al Talh area near Saada was bombed in May 2015. On the same day, the Houthis said they had shot down a Moroccan F-16 fighter jet which crashed near Aleshash.

Denouncing the coalition’s “aggression,” he told MEE he had felt compelled to document retaliatory Houthi attacks against the Saudis and their allies.

In April 2018, Wadi’s brother, Shafeeq, and his brother-in-law were both killed in a coalition air strike in the Asir region, where they were working in logistics, delivering food and supplies to frontline Houthi fighters.

“He left home a month-and-a-half after getting married,” Wadi said of his brother’s death. “I didn’t know how to tell my brother’s wife and my sister that their husbands were martyred.”

Wadi said another brother of his late brother-in-law, who was also working for the Houthis’ media arm as a cameraman, had been killed while reporting on the operation in Najran.

According to Wadi’s account, the man had put down his camera and returned to the fray with his gun as a firefight at one of the captured military sites intensified.

According to Wadi’s account, the man had put down his camera and returned to the fray with his gun as a firefight at one of the captured military sites intensified.

Despite being armed and wearing military fatigues, members of the Houthi media have little in the way of serious protection in their frontline work.

Wadi said that at least 200 Houthi media workers have been killed while reporting on military operations. Though the figure cannot be independently verified, the Houthis’ Al Masirah TV channel often carries footage of the funerals of cameramen killed in action.

Asked why he doesn’t wear a helmet or a flak jacket as protection from shrapnel, Wadi shrugged.

“In the future, God willing, I will try,” he said.

‘I may die at any moment’

In the towns and villages we pass through northeast of Saada we are greeted with suspicion, hostile stares and questions about who we work for.

Some assume we are with the United Nations’ World Food Program, the main aid agency providing food to millions of people on the brink of starvation across Yemen. At the market in Aleshash, a man complained to us that he had only received half a sack of wheat.

It was unclear how much he believed he was entitled to. The WFP usually provides those it supports with a sack and a half of wheat along with oil, sugar and peas, but some of the aid is distributed via local intermediaries.

It was unclear how much he believed he was entitled to. The WFP usually provides those it supports with a sack and a half of wheat along with oil, sugar and peas, but some of the aid is distributed via local intermediaries.

He blamed “traders” for the shortages, though, like others we spoke to, he was not prepared to go into detail, perhaps fearing retribution.

Most dodged questions. One man told us that he was comfortable despite the war, while another said that all he wanted was help to get married.

Despite the shortages, at 10 o’clock in the morning, the market is busy. Most of the shoppers wear Bedouin clothes and carry rifles on their shoulders, and it is hard to tell whether they are Houthi fighters or simply local tribesmen for whom carrying a gun is commonplace.

Sitting on top of an old pickup truck used to sell khat, Abdullah Ahmed Hussein is one of the few who are not armed. A father of eight, Hussein told MEE that he was simply passing time sitting with the khat seller.

“I have no job, no nothing. I am Dhabeh and may die at any moment,” Hussein said, using an Arabic colloquialism for someone bored or tired of life.

“We suffer from a lack of cooking gas and food. There are shortages of almost everything,” Hussein said as a crowd gathered around us.

Hussein said he had heard explosions coming from the border area at the beginning of June. But people in Aleshash thought little of it, he added. The sounds of war have become a backdrop to life in the town, he said.

Tent hospital

Tent hospital

By the time we approach Kitaf, east of Aleshash and an area that has seen recent heavy fighting, there is little other traffic on the road. Our radios are tuned into chatter from the Houthi control room in case a drone is spotted and we are notified to seek shelter under the trees.

In the centre of Kitaf, parts of the town’s hospital have been reduced to rubble. In March, the building was damaged by a coalition air strike which hit a nearby petrol station. At least five children and three adults died, according to Save the Children, which supports the hospital.

An ambulance is parked to the left of the damaged building’s main gate, while a tent remains erected on the other side.

“We received patients inside it in the days following the attack that levelled the hospital,” Ashraf Zaid, a pharmacist, told MEE, pointing at the tent.

The 27-year-old said he was standing near the window of the hospital pharmacy when the attack happened. All he remembers is the sound of warplanes overhead, and then an explosion.

When MEE visited, the main hospital building was still out of use because of concerns about further attacks. Gunships could be heard hovering nearby, and staff said fighter jets were also frequently heard.

When MEE visited, the main hospital building was still out of use because of concerns about further attacks. Gunships could be heard hovering nearby, and staff said fighter jets were also frequently heard.

With nearby fighting also escalating, the Saudi-led coalition had also threatened “stern action” in the aftermath of a missile attack on Abha airport on 13 June that injured 26 people.

“We suffer because of the aircraft. Without them, we would be treating patients properly,” Zaid said.

Another survivor of the attack was the driver of the ambulance, who told MEE he had suffered shrapnel wounds to his head and was now suffering from post-traumatic stress.

From Kitaf, the road continues towards Al Buqaa district, but all those we speak to warn us against travelling any further.

The front line between the Houthis and the Saudi forces cuts across the road about 15 kilometres out of the town and is too dangerous to approach in a car, we are told.

A driver who regularly transports passengers between Saada and Kitaf told MEE that Al Buqaa was under the control of Saudi-backed forces, and that Kitaf was as far as he would now travel.

‘Yemenis used to enter these regions’

‘Yemenis used to enter these regions’

For the Houthi forces fighting in this region, attacks into Saudi territory are more than simply retaliation against the incursion into their homeland by the Riyadh-led coalition.

Many also consider a goal of the war to be the “liberation” of territory that they still claim as theirs.

“As a Yemeni fighter here on the borders, I want to see Abha, Jizan, Asir and Najran returned to us,” said Abu Hakim, our driver.

Yemeni claims to the region around Najran date back to the 1934 Treaty of Taif, which established the border between the newly formed kingdom of Saudi Arabia and the kingdom of Yemen. The treaty was rejected by the founders of Yemen’s republic in the 1960s who vowed to recapture the disputed territory.

The rise of the Houthi movement in the border provinces during the first decade of this century was in part a response to a subsequent agreement between then-Yemeni president Ali Abdullah Saleh and Riyadh in 2000, reaffirming the borders established at Taif, and wider Saudi efforts to curb the independence of the northern tribes.

“Yemenis used to enter these regions with their rifles,” said Abu Hakim, our driver. “There are Yemeni people who still own territories in these regions and have proof-of-ownership documents.”

‘Death to America!’

‘Death to America!’

By contrast with Aleshash and Kitaf, on arrival back in bustling Saada it is almost possible to forget that there is a war going on. Markets are crowded, and there is freedom of movement. But everything is expensive, and prices even for day-to-day items are quoted in Saudi, rather than Yemeni, riyals.

Nor has the conflict interrupted a flow of people from Africa to Saudi Arabia, with many of those making the journey in search of work passing through Saada on their way to the Al Thabet border crossing.

One Ethiopian man who spoke Arabic told MEE he was travelling with two other Africans despite the fact that none of them had passports.

“If the Saudis arrest us, they’ll hold us for two months, then deport us directly to Ethiopia,” he said. Once back home, they would immediately return to Yemen to try again, he added.

Before Friday prayers at the city’s Bin Salman Mosque, the mood is belligerent.

Addressing the worshippers, the preacher says he is proud that the Houthi-controlled Saada governorate welcomes people from all regions of Yemen, contrasting it with the southern port of Aden, currently mostly under the control of Emirati-backed separatist fighters, where he says it is too dangerous for people from the north to travel.

He then exhorts them to join in a raucous chorus of the Houthi slogan, chanting it three times. Only a few fail to respond, but he then repeats it a fourth time, explaining that he has done so to give those who had been hesitant a chance to join in.

“I wonder how there are people who are hesitant to say ‘Death to America,’ even though American aircraft hover over their heads,” he says, ending his sermon with a smile.

Pressmediaofindia

Pressmediaofindia